Material Selection for CCS Pipelines

Introduction

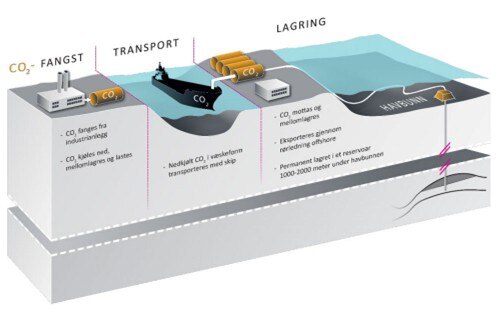

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) is an essential technology for reducing industrial CO₂ emissions and mitigating climate change. The CCS process includes CO₂ capture, compression, transportation, and storage. Regarding the large-scale CO₂ transportation, using pipeline to transport is the most efficient and cost-effective method. However, due to CO₂'s special physical and chemical properties, material selection for CCS pipelines requires different considerations compared to traditional oil and gas pipelines. Therefore, engineers must account for corrosion risks, phase behavior, and fracture toughness when designing CCS pipelines. In addition, it requires the integration of robust monitoring, predictive maintenance, and integrity management strategies to ensure operational safety and economic feasibility.

Fig. 1. Illustration of CO₂ capture, transport and storage. Illustration: Equinor

Potential risks

Compared to gas and oil, pipeline transporting CO₂ presents several challenges:

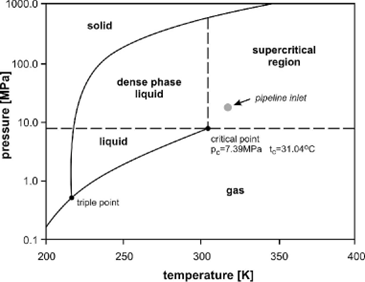

- Phase change risks: CO₂ is typically transported in its supercritical state, where the operation pressure is above 74 bar and temperature is above 31°C . This phase gives the best transport efficiency, combining liquid-like density with gas-like flow properties. However, sudden pressure drop can cause CO₂ to solidify into dry ice, resulting in the pipe blockage and low temperature embrittlement.

- Internal corrosion risks: Generally, pure CO₂ is not corrosive under dry conditions. However, when combined with water or other impurities such as hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), sulfur oxides (SOx), or nitrogen oxides (NOx), it can form highly corrosive acids such as carbonic acid (H₂CO₃), sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄), and nitric acid (HNO₃), accelerating pipeline degradation.

- Running ductile fracture risks: A leak in a CO₂ pipeline can trigger running ductile fracture (RDF), where cracks rapidly propagate along the pipeline. Unlike natural gas, CO₂ has a lower decompression rate, meaning fractures can propagate over extended distance before self-arresting, resulting in catastrophic consequences.

Fig. 2. Phase diagram for CO2 Fig. 3. Illustration of running ductile fracture. Zhu, Eng. Fract. Mech. 2015.148: 260–280

To mitigate the aforementioned risks, pipeline materials shall have high fracture toughness and good resistance to low temperature embrittlement. The pipeline sections in high-risk areas shall have higher wall thickness to resist crack initiation, and crack arrestors shall be installed at certain intervals to prevent fracture escalation. Besides, internal corrosion can be prevented by strict control on moisture level and impurity contents. Using chemical inhibitors and internal coatings can be considered if moisture control cannot be ensured. Additionally, external corrosion protection strategy can be adopted the same way as oil and gas by using protective surface coating together with cathodic protection.

Generally, for the long-distance large-scale CO₂ transportation, the carbon steel X65/X70 is the most used pipeline material due to its high strength and cost-effectiveness. However, it requires strict dehydration to prevent internal corrosion. For high-risk areas or environments with corrosive impurities (H₂S, SOx, NOx), corrosion-resistant alloys such as 316L stainless steel or Nickel-based alloys are necessary, though the cost is significantly higher than carbon steel.

Pipeline maintenance strategy:

Even with optimal material selection and strict dehydration control, implementing a comprehensive maintenance strategy is essential to ensure pipeline integrity and long-term operational performance. An effective integrity management plan should cover regular inspection strategy, impurity monitoring, and risk assessment methodology.

Key aspects of this strategy include: 1. Non-destructive testing and inline inspection to assess coating disbondment, wall thickness loss, and pitting corrosion. 2. Cathodic protection system monitoring by tracking the anode consumption. By monitoring the anode depletion rate, the potential coating failure and localized corrosion issues can be identified. 3. Continuously monitoring impurities and moisture in CO₂ gas to ensure the purity follows the pipe design specifications and to prevent internal corrosion and phase instability. 4. Pressure and temperature monitoring to avoid phase change and low temperature embrittlement.

Furthermore, integrating Failure Mode, Effects, and Criticality Analysis (FMECA) and Risk-Based Inspection (RBI) into maintenance plan allows for a systematic evaluation of potential failure mechanisms and their consequences. By prioritizing high-risk areas, inspection schedules can be optimized, leading to reduced downtime and enhanced long-term pipeline safety.